Last updated: April 22, 2022

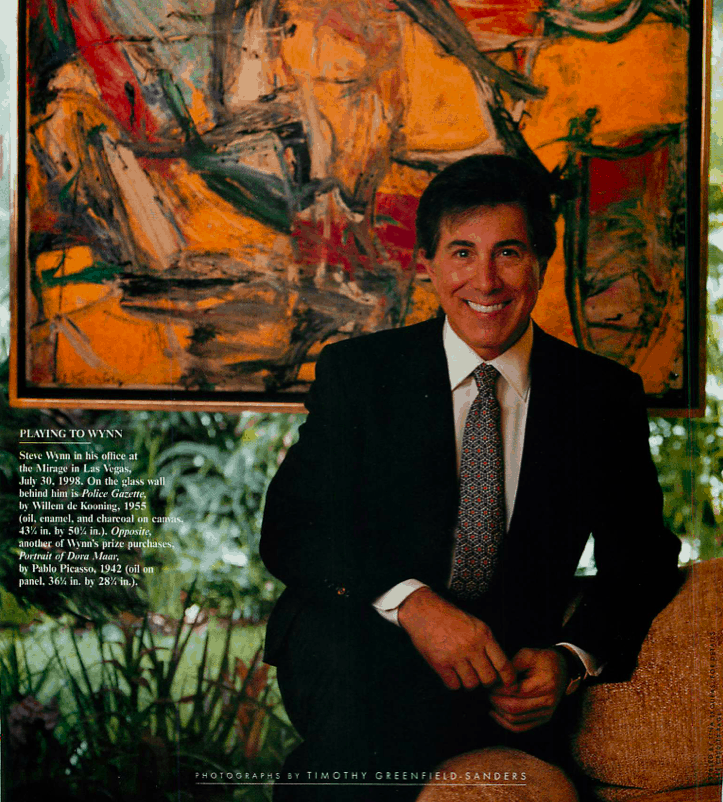

Found this in the October 1998 issue of Vanity Fair. I think Steve Wynn is pretty cool and wanted to share for others who might be searching. Email me if you want the article PDF. —- Nick, Jan 22, 2014

Mr. Steve Wynn Builds His Dream Collection

As published in Vanity Fair, 1988

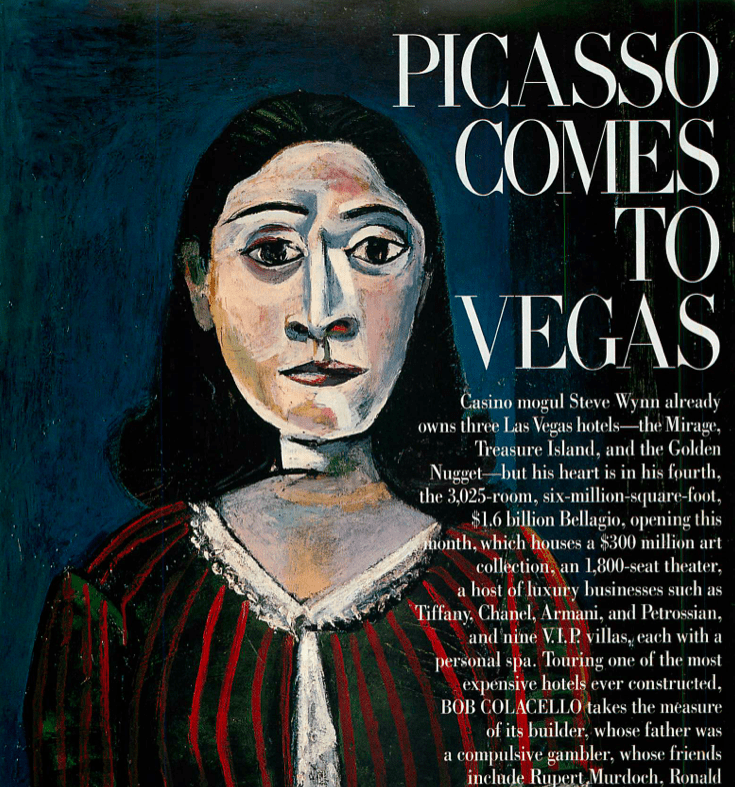

With sources drying up and prices skyrocketing, it would seem an insane ambition to build a major collection of 19th- and 20th-century masterpieces. But Steve Wynn has defied the odds to present Las Vegas with a monument to serious culture, the Bellagio Gallery of Fine Art, in his new hotel. Tracing $300 million in acquisitions, from a Japanese-bridge painting by Monet to a Picasso portrait of Dora Maar, JOHN RICHARDSON discovers that a degenerative eye disease hasn’t stopped Wynn from focusing on beauty.

To embark on a collection of major paintings by the giants of Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and the Schools of Paris and New York, as Stephen A. Wynn is doing, would seem at this late date to be lunacy, given that sources are drying up, that prices for even secondary works are rising from seven digits to eight, and that Wynn, who has had no previous experience in the notoriously tricky art market, is afflicted with the degenerative eye disease retinitis pigmentosa. As usual, however, the infinitely imaginative, not to say combative Wynn has triumphed over all the odds. In less than three years, he has surprised everyone by assembling an increasingly stellar microcosm of 19th- and 20th-century art that would put most museums to shame. Although these 40 or so acquisitions have probably cost Wynn and his corporation in the neighborhood of $300 million, he has gone about his business so skillfully that many of the purchases he has made in the name of the Bellagio Gallery of Fine Art—a miniature museum at the heart of his new hotel—could be resort at a profit.

Why has Wynn made this costly commitment to modern art?

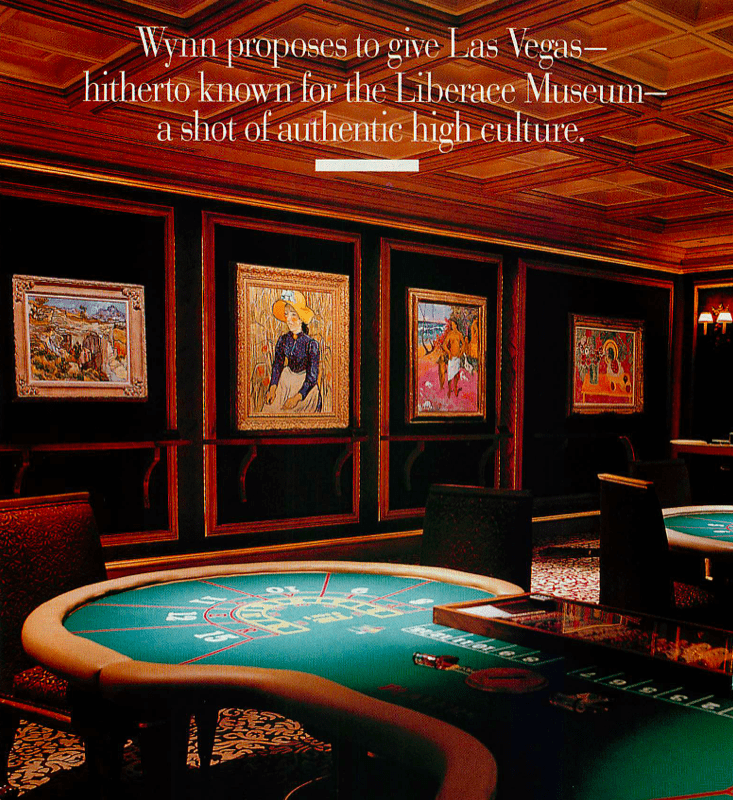

In the interest of culture, elegance, and class, he would say. That Las Vegas, the city where he has established his empire, is synonymous with kitsch, as opposed to culture, is a truism that satirists never tire of pointing out. Wynn intends to change that. He wants his new mega-project, the Bellagio, to be more than a resort hotel, more than a casino or an entertainment center. In the past he has given the public not only Siegfried and Roy and their Secret Garden roar with white tigers but also a two-and-a-half-million-gallon tank of bottle-nosed dolphins and a spectacular auditorium, which has enabled Cirque du Soleil to revolutionize the whole circus concept. Now Wynn proposes to give Las Vegas, hitherto known to the public for the Liberace Museum, a shot of authentic high culture. In a city where virtually everything—Eiffel’s Tower, Manhattan’s skyline, Caesar’s Palace—prides itself on being a fake, he is determined that visitors to the Bellagio Gallery should at long last encounter authentic masterpieces face-to-face and become born-again art-lovers like himself.

Wynn is convinced that art will improve the popular perception of Las Vegas and will help propel the city into a 21st-century version of one of the great casino resorts of the Belle Époque (Monte Carlo is the most obvious example), where visitors in search of diversion and grand luxe can count not only on every kind of gambling (from nickel slots machines to baccarat at $150,000 a card) but also on sensational entertainment, stylish shops, prestigious restaurants, and, with luck and the right incentives, elegant company. Wynn sees the art gallery as his flagship in this venture.

To define and refine the Italianate concept of this enterprise and bring it into sharper focus, Wynn has invented a noble Italian couple, Count and Countess Bellagio, “heirs to a hotel-and-banking fortune.” The Bellagios supposedly settled in Nevada in the 1870s–desert air has been prescribed for the count’s asthma–and built a great villa with formal gardens and an artificial lake. To accommodate hordes of distinguished friends, the family subsequently built the 100-room Albergo Bellagio and the Bellagio Nevada villas. Later the estate fell into disrepair, but Wynn came along and acquired it. In his scenario he “created a lake on Las Vegas Boulevard [and] rebuilt the villas and extravagant grounds and gardens exactly as they had been.” Voilá Bellagio!

Since art collecting had played a major role in the Bellagios’ way of life, it would play a major role in Wynn’s concept. The only problem: their paintings would have been old masters–massacres, miracles, martyrdoms–which would have been “much too heavy for a casino,” Wynn says. And so he speculated that a family as discriminating as the one he envisioned would also have been pioneer collectors of Manet and Monet, Degas and Renoir, van Gogh and Gauguin–the artists he was determined to acquire.

Although Wynn knew all about buying valuable property, he knew little about buying valuable paintings. “I didn’t want to wander into just any gallery,” he says, so he canvassed his collector friends. Whom should he get to advise him? Everyone agreed that Bill Acquavella, the New York dealer, would be the best mentor for him. The two men had never heard of each other, but each was intrigued by the other’s potential. In no time Acquavella, who has a superb private collection of his own, set to work fulfilling Wynn’s dream. “Bill taught me the difference between good and great,” says Wynn. “No problem,” says Acquavella. “Steve has a gut feeling for quality. Also, he knows that you have to pay a premium for it. He knows that quality holds its value, and bargains don’t.” He cites the Bellagio’s Japanese-bridge painting by Monet. The pile of money that it cost Wynn two years ago is peanuts compared with the $33 million that someone paid for a similar version this summer.

The first acquisition that Acquavella masterminded for Wynn was Renoir’s delightful Young Women at the Water’s Edge. It is a quintessential Impressionist subject–the epitome of summer. Two women sit on the bank of the Seine watching a man row by. Renoir has endowed the light with such a sparkle that we can share the women’s enjoyment at being out in the fields on this beautiful day, just as we can share the artist’s delight in finding a sensuous equivalent for every passage in the idyll. To use the phrase that cannot be applied to today’s art, this is French painting at its most life-enhancing.

Wynn went on to buy another ravishing Renoir, the preliminary version of the artist’s famous La Loge: a couple in a box at the theater or opera during an entr’acte. In the background the artist’s brother, in a white tie, leans forward to peer through his opera glasses at the audience, while his gorgeously dressed companion preens eye-catchingly in the front of the box. A respectable lady would have been more circumspect; Renoir presumably intended the subject of this painting to be perceived as a courtesan. Research reveals that she was a professional model known as Gueule-de-Raie (Fish Face).

The Bellagio’s beautiful Degas pastel–of a solitary dancer, who has detached herself from the corps de ballet to accept a bouquet–had been hidden away in a Rothschild-family collection for the last 80 years until Wynn managed to acquire it. I will never forget coming upon it for the first time–how it lit up a dark room in a treasure-filled Paris apartment and lingered on in memory as one of Degas’s consummate ballet scenes. The Bellagio’s other sublime pastel–one of the dazzling portraits Manet executed towards the end of his life–is a no less astute acquisition. Quite apart from its pristine delicacy and freshness, this work has the literacy distinction of belonging at the very heart of the greatest French novel of this century, Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past. The sitter, Suzette Lemaire, was one of the girls on whom Proust based the character of Gilberte, one of the narrator’s great loves. Proust had gotten to know Suzette through her formidable mother, Madeleine Lemaire, who presided over the most socially star-studded salon in Paris. The mother also inspired a central character in the novel: the relentlessly manipulative, insatiably snobbish, utterly fascinating hostess Madame Verdurin. When not organizing her scintillating Tuesdays, the mother painted roses, as would the daughter. As one of the mother’s lovers, the younger Alexander Dumas, observed, “No one, except God, has created more roses.” Her watercolors of roses were snapped up by social climbers, who hoped to be rewarded with invitations to her salon. Charles Ephrussi, the connoisseur who arranged this commission and was given another version of the portrait for his pains, was also close to Proust, and likewise contributed some of his traits to yet another central character in the novel, Charles Swann.

Two of the most important paintings in the Bellagio collection are by van Gogh, and date from the last year of his short life. Entrance to a Quarry was painted in October 1889, when the artist was confined to the asylum at Saint-Rémy in Provence, after cutting off his ear. There has been several further crises and attempts at suicide (swallowing paint or kerosene), but now that he was getting better he was allowed out into the countryside and proceeded to paint some of the wildest and most agitated landscapes of his career. Van Gogh described the painting in question to a friend: “Pale lilac rocks in reddish fields, as in certain Japanese drawings.” One of the artist’s odder misconceptions–born of his passion for Japanese prints–was the Provence looked like Japan.

The Bellagio’s other van Gogh–a powerful portrait of a peasant woman wearing a straw sunbonnet and seated in a wheat field–was painted a few months later. By this time van Gogh had gone to stay at an inn in Auvers, an artists’ colony some 20 miles away from Paris, in the hope that the local doctor, a kindly psychobabbler with a passion for modern art named Gachet, would be able to cure him of his suicidal depressions. Gachet turned out to be useless. “We must not count on [him] at all,” van Gogh wrote his brother. “First of all he is sicker than I am.” But at least Gachet kept the artist painting–hence all those heart-stopping Auvers landscapes. In mid-June, van Gogh wrote Gauguin that he intended to paint some portraits against the “vivid yet tranquil background of nothing but ears of wheat with green-blue stalks,” and he embarked on this, his penultimate portrait. He used bright color, he told his sister, as a means of expressing and intensifying character. A month later he had another one of his attacks. He went out into the wheat fields, apparently to paint, and then shot himself with a revolver just below the heart. He managed to struggle back to the village inn, where he died two nights later. Gachet, who was an amateur artist, went to paint several “van Goghs” himself, which have only recently been unmasked as fakes.

Like the Bellagio van Goghs, the Gauguin dates from the last year of the artist’s life. By the time he had left Tahiti–on the grounds that it had been spoiled by missionaries and colonial officials–to live in the remote Marquesas Islands, where cannibalism was still thought to flourish. In this primitive Eden, Gauguin wrote a friend, “the savage atmosphere and complete solitude will give me a last burst of enthusiasm before dying.” It did. The canvases he painted there are rife with mystery and magic. The long hair and prominent breasts of the androgynous man at the center of the Bellagio painting identify him as a Mahu. Mahus were effeminate males whom the Marquesans raised from childhood as women and held in some reverence. For Gauguin they signified the enigma of male sexuality. Androgynes were figures of magical power, as he wrote in Noa Noa, his poetic text about Polynesian customs.

This painting exemplifies the enormous influence that Gauguin exerted on Picasso’s early work. Picasso would have seen the Gauguin in 1904 at Vollard’s gallery, where they were both exhibited. Two years later, Picasso followed Gauguin’s example and went in search of primitivism. He found it in Gósol, a virtually inaccessible village high in the Pyrenees. And there he adapted the design of the Bellagio Gauguin for the beautiful Rose Period allegory in the Barnes collection, outside Philadelphia. In the place of the Mahu, Picasso has set his mistress, Fernande Olivier, combing her hair, with a goat on one side and a child on the other. No wonder Gauguin’s Parisian followers came to believe that the spirit of their master, who had died in 1903, lived on in this young Spaniard.

When Acquavella showed Wynn Picasso’s 1942 portrait of Dora Maar, one of the most famous images of the artist’s tortured model, Wynn’s taste and approach to collecting underwent a total transformation. Up till then he had found modernism, especially Picasso’s, baffling. Acquavella set out to change this. “It’s a difficult painting,” the dealer said of this daunting portrait. “I’m not trying to sell it to you. I just want you to understand what is so great about it.” His eloquence prevailed: Wynn was amazed to find Picasso’s image obsessing him. It had a presence that was almost palpable. Dora was not just staring at him; it was as if she was physically there, and her life force had merged with the artist’s. Wynn took Acquavella aback by asking for a transparency, then returning again and again to study the painting. Meanwhile, he had bought a more conventional Picasso, a fine early landscape, at auction. But it was infinitely more challenging Dora Maar that continued to haunt him. In the end Acquavella arranged for Wynn to acquire it in exchange for the landscape plus a substantial amount of cash.

Although this portrait is one of the least distorted of the hundreds of Dora Maars that Picasso executed, the subject claimed not to like it. It had started life as a modish likeness of her by the artist’s old friend and sometime court jester, Jean Cocteau. Picasso had the highest regard for Cocteau’s wit and verbal dexterity but the lowest opinion of his ability as a painter and of his opportunistic courting of the Germans during World War II. Picasso could not resist humiliating Cocteau. Encouraging him to paint the woman he had immortalized–above all in his anti-Fascist masterpiece, Guernica–was typical of Picasso’s teasing. Sure enough, after pretending to like what Cocteau had done, Picasso announced that “there’s one little detail that could be made better…Jean will never notice.” After working away for half an hour or so, this most competitive of artists succeeded in painting out the Cocteau. “It was a perfectly terrible picture,” he announced. “I’ll have to take it to my place and finish it properly.” Finish it he did; once again he had transformed dreck into great art.

Picasso’s view of himself as a shaman, and his art as having a magic function, is nowhere better exemplified than in the magnificent portraits of Dora Maar, in which he seduces her, makes love to her, enslaves her, and then finally destroys her. At the time, Picasso was working on the Bellagio portrait, Dora was on the worst terms with her mother. In the midst of a terrible fight with her on the telephone one evening, the mother suddenly stopped talking. Because of the wartime curfew, there was nothing Dora could do. In the morning she went to check and found her mother lying on the floor, as dead as the telephone clutched in her hand. Dora was traumatized with guilt, but, for a change, Picasso, who had nicknamed her La Pleureuse (the Weeping Woman) and had repeatedly exploited her tears in his work, portrays her all the more effectively without visible tears. He has internalized them, bottled them up. The painting was not really of her, Dora said; she would never have worn a dumb green-and-orange striped dress. Bunkum. Her reservations about the painting surely stemmed from the fact that it was too much of a psychic likeness rather than too little of a sartorial or physiognomic one. For the few of us who went on seeing this tragic figure after she became a total recluse, this portrait is Dora to the life.

Within 30 days of buying the Dora Maar, Wynn says, “I was finished with Renoir. I now wanted all the Picassos I could get.” He went after The Dream, the famous painting in the Ganz sale last November at Christie’s, which sold for $48.4 million, but he ended up as the underbidder. Since then he has assembled a dozen mostly late paintings by Picasso as well as some 40 or 50 of his ceramics. By the time this article appears, he will almost certainly have acquired more. Meanwhile, Wynn has become a good friend of Francoise Gilot and her son, Claude Picasso, whom he recently commissioned to design the furniture and carpets for the hotel’s Picasso restaurant. The restaurant, which looks out over the huge Italianate lake that Wynn has created, will be a showcase for most of the paintings he owns by his favorite artist.

The Dora Maar portrait inspired Wynn to switch the main focus of the collection from 19th- and 20th-century art. The three Matisses he acquired for the Bellagio include a wonderfully sensuous 1940 still life of a pineapple and anemones; the Modigliani is a small but incisive portrait of Paul Guillaume, the dandified dealer who had discovered the artist; the Miró is a famous Surrealist icon, Dialogue of Insects, of 1924-25, in which the artist gets as close as possible to his native Catalan soil and adopts the viewpoint of the ants–thus the surreal magnification of the grain stalk. The Bellagio has also acquired two celebrated modern sculptures: one of Brancusi’s polished bronze heads of Mademoiselle Pogany and Giacometti’s Man Pointing, which James Lord, the artist’s biographer, considers a self-portrait, on the grounds of likeness and the fact that this is the only figure in the artist’s oeuvre to possess a penis, albeit a vestigial one. Giacometti has whittled this sculpture to little more than an armature: a monument to human fragility and solitude. Its very thinness makes the space around it seem tangible and infinite as water.

Emboldened by the acquisition of these 20th-century classics, Wynn has raced even farther ahead, and in the last few months has assembled a very fine collection of contemporary American painting, from Abstract Expressionism to Pop art. Once again, he has pounced on great works by great names: Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein. Pollock’s large drip paintings–which the critic Harold Rosenberg famously described as “apocalyptic wallpaper”–are notoriously hard to come by. Nevertheless, Wynn has managed to acquire one of the most dense and complex examples. Pollock worked and reworked Frieze over a period of three years, before his drunken death in an automobile accident in 1956. Robert Rosenblum, author of an essay on Frieze in the Bellagio catalogue, sees this tangled, tortured painting as the artist’s swan song.

De Kooning’s Police Gazette is no less of a landmark. It was painted in 1955 at a key point in his early development, when he was working in a style that partakes of both abstraction and figuration. In the course of being scraped down and reworked, Police Gazette changed from being the image of the nude into a tantalizing hybrid: which art critic Peter Schjeldahl describes in the catalogue as “remnants of a savage goddess in the crashing surf of paint.” The painting was done around the same time as the Bellagio’s beautiful Small Red Painting, by Robert Rauschenberg and the de Kooning in the context of the celebrated drawing which Rauschenberg had recently persuaded de Kooning to give him, simply so that he could erase it (a patricidal and iconoclastic act that took 40 erasers to complete), these two works make a curiously complicit pair– a complicit trio if we include another Bellagio treasure, Jasper Johns’s abstruse Highway of 1959. This is one of the earliest works in which Johns introduced autobiographical references, in this case his first experience of driving a car at night.

As I write, Wynn continues to acquire items on an almost daily basis: Johns’s Flag on Orange Field II (1958), Warhol’s Campbell’s Elvis (1962), Cézanne’s great late portrait of his housekeeper, Franz Kline’s masterly August Day (1957), Lichtenstein’s Torpedo…Los! (1963), and “something very important we can’t yet tell you about,” he says. Wynn should also acquire a lot more gallery space, for it is all too apparent that he is completely hooked on art collecting. “I never had so much pleasure in my entire life,” he says. “Paintings have come to mean much more to me than cash.” With his acumen, enthusiasm, and energy, Wynn may well turn out to be the next Norton Simon, especially now that he has added the illustrious Edmund Pillsbury, the former director of the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, to his roster of consultants.

As for Wynn’s eye problems, he makes light of them. He says his condition was diagnosed more than 25 years ago, so he is inured to the prospect of diminishing vision. When asked whether retinitis has affected his art collecting, he answers by looking across the room at a painting he is seeing for the first time and describing it in minute detail. Though his field of vision is so peripherally limited that obstacles have to be brought to his attention, his sight seems unimpaired when he focuses straight ahead. He keeps himself in fantastic shape and continues to ski like a demon. “Thirty-eight days on the slopes this year,” he says. And that is not all. As I take my leave, what are he and Acquavella discussing, besides the prospect of further acquisitions, but golf.